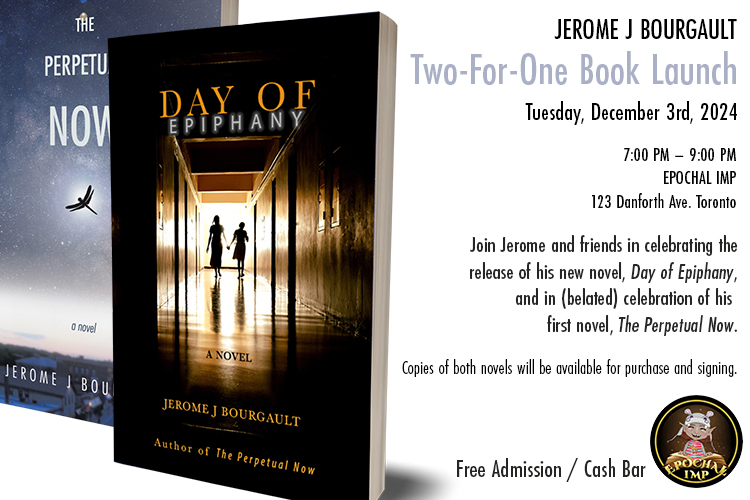

Here is what the judges for the Whistler Independent Book Awards had to say about Day of Epiphany. My profound gratitude to Darcie Friesen Hossack and Stella Harvey for their support and enthusiasm for my novel!

Read this book.

No, really. The review could end right there. But since I want to make sure everyone buys multiple copies of Jerome J Bourgault’s Day of Epiphany (for yourselves, for family, especially for your local library), I’m going to use every word of this space given to me.

Day of Epiphany accomplishes everything that brilliant, important literature is supposed to do: It is beautifully rendered. It brings its characters to light and life, with form and breath. It informs. And it engages the reader’s empathy and their moral compass, orienting it towards both past and present injustice.

The injustice in this novel is profound. In Québec, in the 1940s and 50s, when the Sainte-Madeleine Institute (orphanage) burns down in the middle of the night, killing several children, a perfect storm of religious, governmental and societal cruelty gathers strength around the survivors.

“… children who died… were the embodiment of sin,” Bourgault writes, “… the sin of their unwed mothers.” And with that, when the institute is rebuilt as a psychiatric hospital, and the children “reclassified” as mental patients to garner more funds from Québec’s corrupt premier and its purse, the horrors begin for those on the “bottom rung of the social latter… (with) no rights under the law.”

Beginning as a sort of confession, Day of Epiphany is ultimately Sister Cassandra’s story. And yet, in the various circles of hell that surround her, we experience the lives of three young girls, along with others who are both caught up in the same awake nightmares, and those whose purpose it is to sustain those nightmares. And while we experience in this novel forced institutionalization at nearly its worst, we also come into the circles of “powerful men who paid extra for discretion and even more for youth.”

Darcie Friesen Hassock

A searing indictment of a shameful and violent time in Canada’s history, Day of Epiphany chronicles the plight of the children of an orphanage, later turned mental institution through the financial support of Quebec’s Duplessis government at the time. Told mostly from a nun’s perspective, we meet many of the characters she is charged with, feel sister Cassandra’s guilt as she sees what is happening to the children, and cheer for those children who refuse to bow down to the neglect, torture, and abuse they are subjected to. I felt the innocence of the children when again and again, they asked, “what did we do wrong?” And I also felt incredible anger and disgust as I turned page after page to witness the abuses dispensed by nuns, priests and doctors who basically experimented on these children. This was an upsetting read, one filled with strong characters; difficult, yet necessary details and lots of suspense. Everyone should read this book and understand this despicable period of Canada’s history in the hopes we never, never let it happen again.

Stella Harvey